Links to recordings from this day of the user meeting are at the bottom of this post.

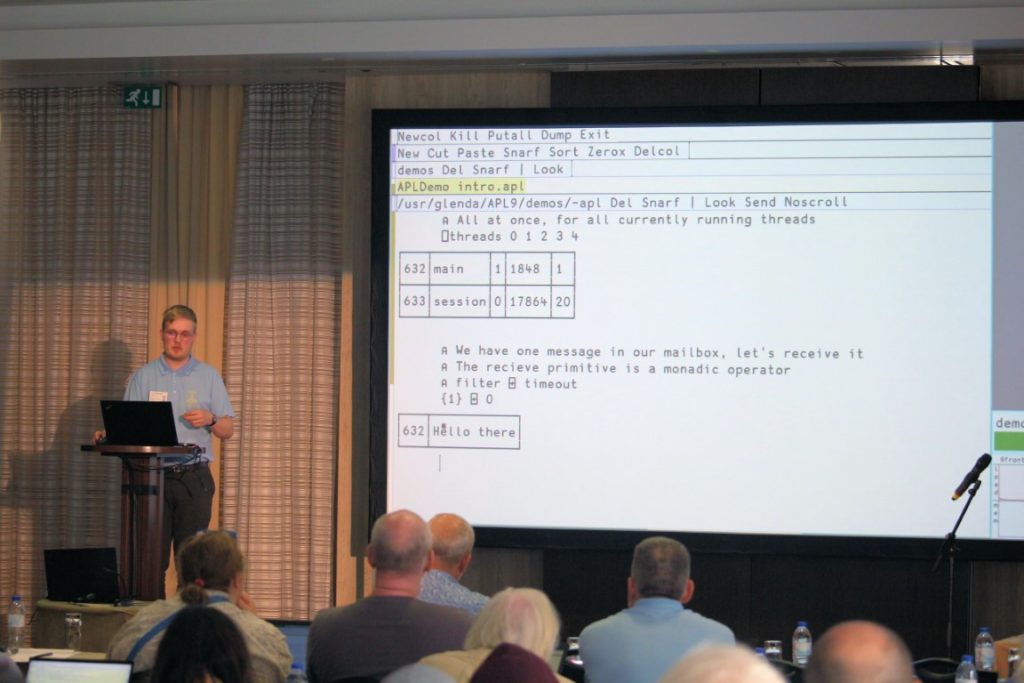

Automation, architecture and performance were throughlines of the second day of presentations. Lars Stampe Villadsen from SimCorp A/S provided some advice on how to write tests and gave a live demonstration of a small testing framework together with continuous integration tools which run the test suite every time a change is committed to the project – useful for when we forget to run some tests locally.

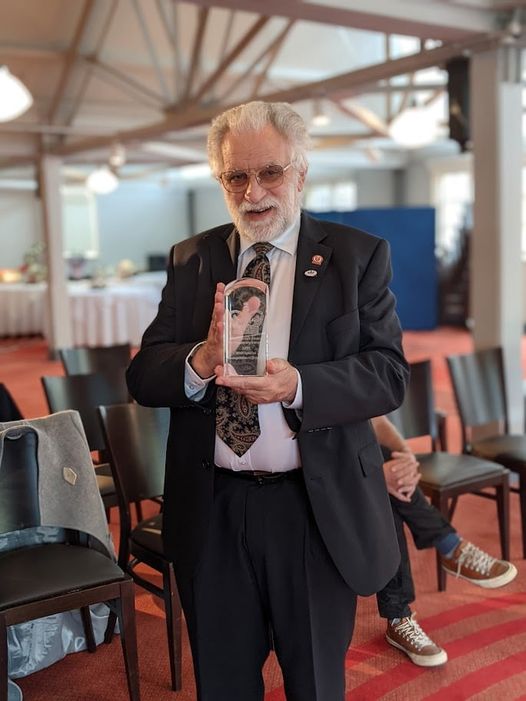

Lars Stampe Villadsen talks about testing.

Norbert Jurkiewicz presented his “10,000 ft overview” of automation processes used by The Carlisle Group and described some of the complexities of building distributables according to varying requirements for different customers. He discussed some of the cost considerations to be made when using Amazon Web Services (or any cloud computing service) to leverage lots of computing power to do builds quickly.

Norbert Jurkiewicz discusses automation architecture.

This was followed by Michael Baas with a similar issue viewed from a different angle. He talked about using the ]DTest testing framework to produce code coverage reports – showing which lines of code had actually been executed when running a test suite – and also automating testing across different platforms and versions of the Dyalog interpreter.

![Michael Baas shows us the ]DTest framework](https://www.dyalog.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/IMG_2878-Medium-1024x683.jpg)

Michael Baas shows us the ]DTest framework

Changing tack, we heard the story of getting to grips with semi-global variables in a multithreaded application. Elena Pavarotti of SimCorp Italiana talked about her experience trying to imagine clearly what a complex system is doing so that it is easier to reliably refactor and adapt it to talk to new external systems.

Elena Pavarotti on managing complexity in SimCorp Sofia.

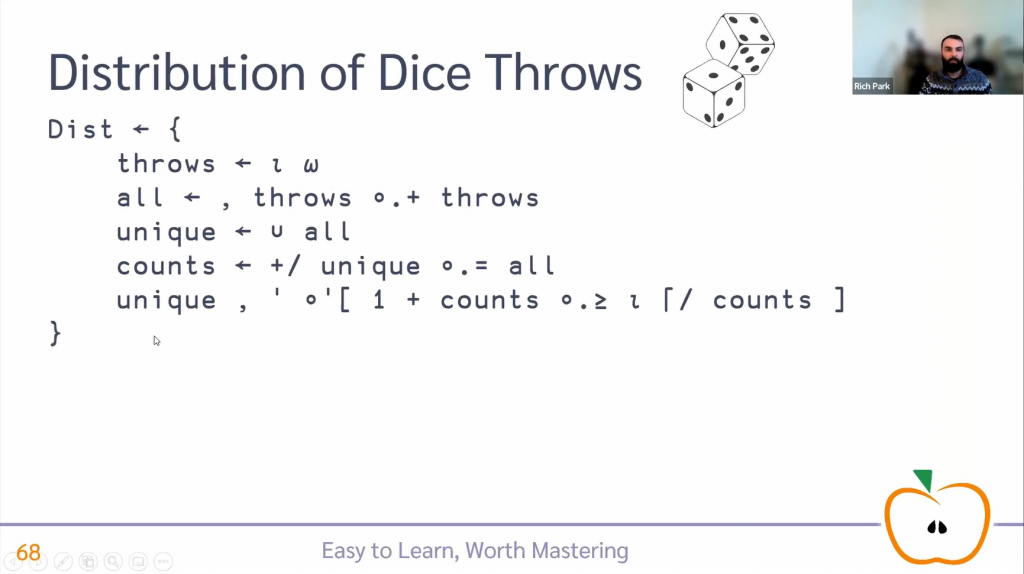

Rodrigo Girão Serrão then told us how himself and Aaron Hsu had implemented a U-Net Convolutional Neural Network from scratch in APL. The comparisons between their implementation and industry standard libraries was very interesting, and then seeing the mapping from diagrams to code showed us how the APL becomes a natural way to express the data flow involved in the system.

Rodrigo Girão Serrão walks us through the U-net CNN in APL.

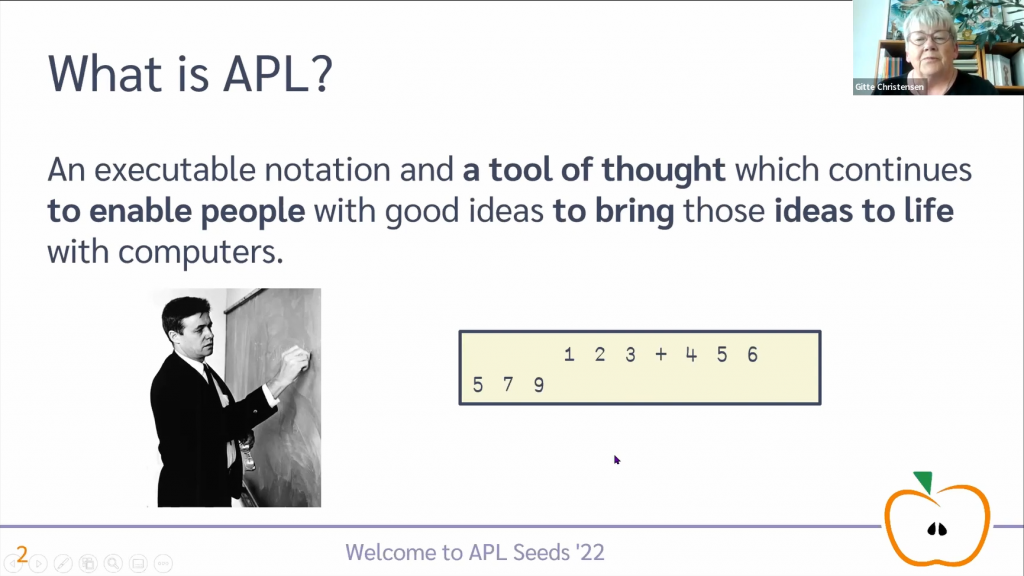

Delving deeper into more intellectual musings, Justin Dowdy of Semantic Arts – also known for his work on the April APL to Lisp compiler and the May bridge between Dyalog and Clojure – drew some interesting analogies between the Resource Description Framework, used for representing data relationships as ontologies, and points raised in Iverson’s paper Notation as a Tool of Thought.

Justin Dowdy compares Notation as a Tool of Thought and concepts of Data Semantics.

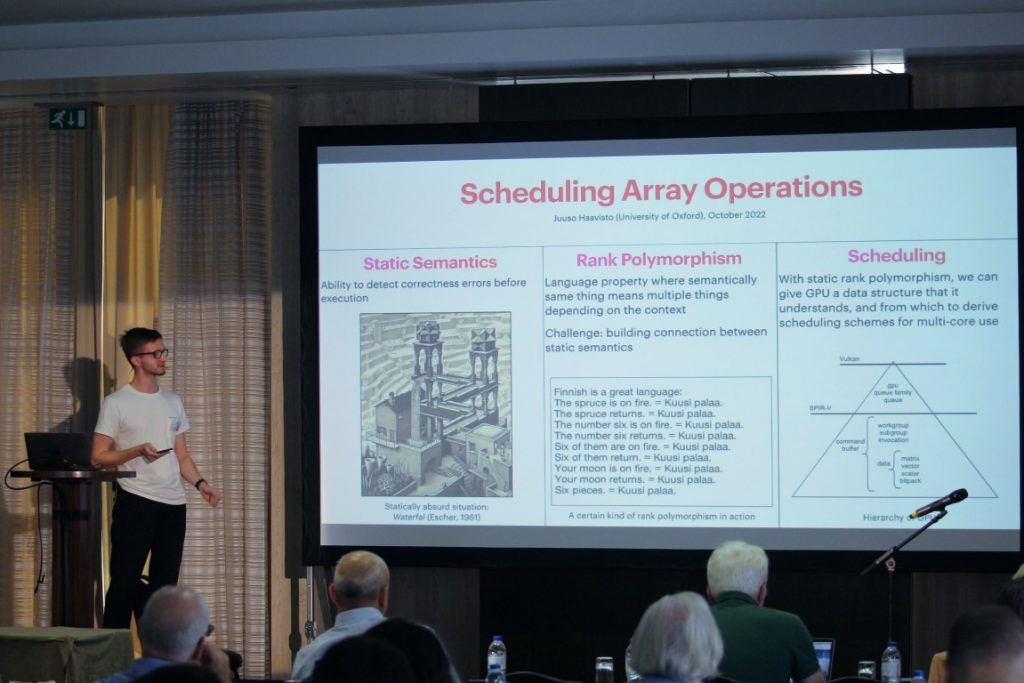

Juuso Haavisto is a DPhil student at the University of Oxford. He brought up some hot topics in computer science academia – static analysis, rank polymorphism and scheduling for multi-core systems – that he believes can be tackled effectively if we can learn to make the computer think a bit more like an APLer.

Juuso Haavisto with three hot topics in computer science academia.

The theme of performance continued when Vali-Matti Jantunen from Statistics Finland compared the performance of some short APL phrases across several versions of Dyalog. Of course, this can be important in an application like PxEdit which processes thousands of text files; a fraction of a second difference processing a single file can lead to several minutes across a job.

Vali-Matti Jantunen on Dyalog performance across versions.

We hope Veli-Matti will forgive us for the performance regressions found in v18.2 (although not slower than v17.1). However, for us it was no surprise, and next Karta Kooner reflected on some of the assumptions made when changes, intended to improve performance, had been implemented over the lifetime of Dyalog APL. He is looking for volunteers to run a version of the interpreter which can gather usage statistics, so please get in touch if you can do this.

Karta Kooner analyses performance in the interpreter.

Presenting the final features of his special Dyalog ’22 Conference Edition of the interpreter, John Daintree talked about the state of asynchronous programming in the interpreter now. Eventually he showed us an interface, in the from of an ⎕AWAIT system function, to unify Spawn (F&⍵) threads, .NET Tasks and Futures and Isolates.

John Daintree with some ideas about asynchronous programming.

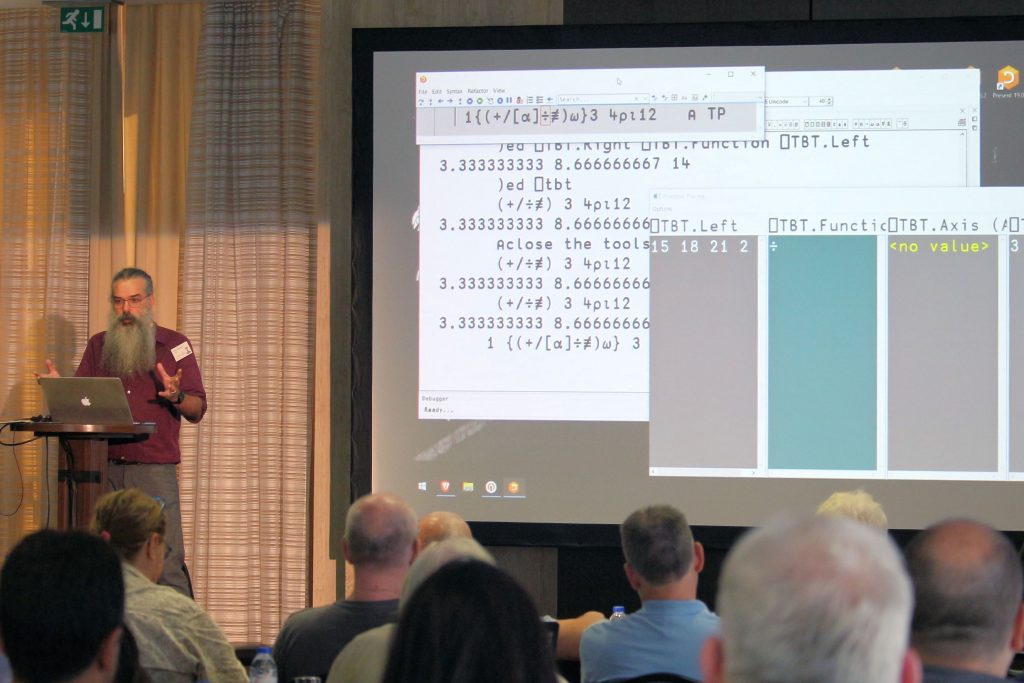

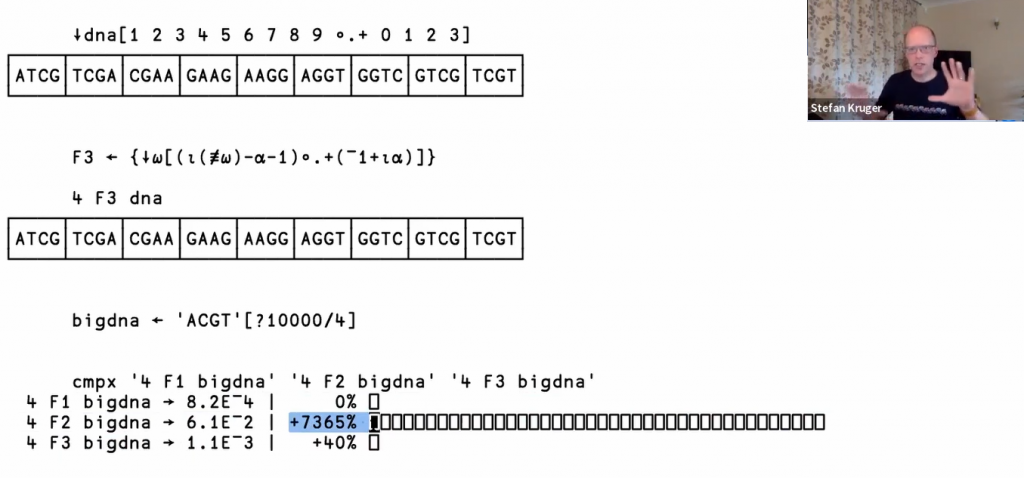

Finally, Aaron Hsu’s Co-dfns report showed a new public API for the parser which could be useful for static analysis of existing code and better error reporting within co-dfns. The new code generator written in APL opens the door to targeting more platforms more easily in the future.

Aaron Hsu presents an update on co-dfns.

Today’s presentations (links to recordings will be added as they become available):

- U06: From “I Developed and Tested It” to “I Developed, and My CI Tested It” – Lars Stampe Villadsen

- U07: Automating Application Builds with AWS – Norbert Jurkiewicz

- D07: Test Your Code! – Michael Baas

- U08: Semi-Globals and Multi-Threading are Like Chalk and Cheese – Elena Paviotti

- D08: Implementing the Convolutional Neural Network U-Net in APL – Rodrigo Girão Serrão

- U09: APL on the Side – Justin Dowdy

- U10: Scheduling Array Operations – Juuso Haavisto

- U11: Performance of Dyalog APL – A Historical Perspective – Veli-Matti Jantunen

- D09: Performance Improvements in Set Operations – Karta Kooner

- D10: 2022 Conference Edition Part 3a – Future(s) – John Daintree

- D10: 2022 Conference Edition Part 3b – Future(s) – John Daintree

- D11: Report on Co-dfns – Aaron Hsu

Follow

Follow

Karta joined Dyalog in April, and is yet to meet anybody in person although he’s been told that this is not necessarily a bad thing! After completing his doctoral degree in theoretical physics, Karta stumbled upon Dyalog and APL entirely by happenstance. Being often captivated by things that look unfamiliar to him, and having an interest in most things, it was a code golf question that was answered in a strange, yet mathematical-looking language that took him to the profile of the poster, who happened to mention they were employed by Dyalog and currently hiring. He sent an email enquiring about the opportunity and, several remote interviews later, was happy to be hired as a C/C++ developer working on the interpreter.

Karta joined Dyalog in April, and is yet to meet anybody in person although he’s been told that this is not necessarily a bad thing! After completing his doctoral degree in theoretical physics, Karta stumbled upon Dyalog and APL entirely by happenstance. Being often captivated by things that look unfamiliar to him, and having an interest in most things, it was a code golf question that was answered in a strange, yet mathematical-looking language that took him to the profile of the poster, who happened to mention they were employed by Dyalog and currently hiring. He sent an email enquiring about the opportunity and, several remote interviews later, was happy to be hired as a C/C++ developer working on the interpreter. In his spare time, Karta enjoys expanding his knowledge of both scientific and technical pursuits, and tinkering around with software and hardware systems, amongst his eclectic interests. When not found reading papers or learning an unfamiliar branch of mathematics, he will be caught thinking of a new engineering project to occupy his time, or stumbling through learning a new language, or maybe just delighting in the latest vixra paper.

In his spare time, Karta enjoys expanding his knowledge of both scientific and technical pursuits, and tinkering around with software and hardware systems, amongst his eclectic interests. When not found reading papers or learning an unfamiliar branch of mathematics, he will be caught thinking of a new engineering project to occupy his time, or stumbling through learning a new language, or maybe just delighting in the latest vixra paper.