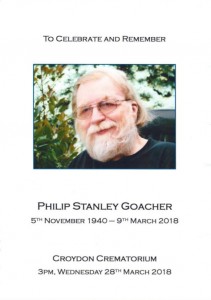

I attended Phil Goacher’s funeral yesterday. He probably had no idea of just how much he would influence the development of APL. I first met Phil at W S Atkins which is a large UK engineering consultancy. There was a sub unit called Atkins Computing which provided internal computing support to the engineers and, crucially, provided a time sharing service to external users. He became my manager when I moved from supporting the transportation program suite to the brand new APL team.

Phil was more manager and business man than programmer but he had an engineering background in Gas distribution and thus the mathematical bias that seems common to APL users.

Phil was the sort of man with an eye for a business opportunity and when a advert appeared from someone who wanted to set up an APL consultancy with a limited objective to provide resources to Rank Xerox (UK arm of Xerox Corp) he turned up along with half his team. Phil was a wheeler dealer type and had already talked to the recruiter, persuaded him that he could manage the team, and then interviewed the candidates. So I wound up being interviewed by my existing manager. Following this Phil decided we only needed a salesman and we could set the consultancy up with a much wider remit. Phil recruited Ted Hare who was one of Atkin’s top salesmen and Dyadic Systems was born.

Phil did all of the necessary legal and administration to get Dyadic off the ground and became the company’s administration guy. He bought an Apple 2 with VisiCalc so was early into the spreadsheet concept. It must be said that all five of the people who started Dyadic were “early adopters” by nature.

Dyadic was quite successful as an APL consultancy but wanted to do more. I am not sure who instigated it (I was too busy consulting) but it was probably Phil’s idea to develop an APL of our own. Knowing Phil this was probably a business eye and a request from Pam Geisler who was Pauline Brand’s sister (Pauline was an early recruit that we “acquired” from Atkin’s) but, more importantly, high up in the management of Zilog. Zilog was developing a new 16 bit chip, Z8000, that was going to push them up market from the 8-bit chip with which they had had enormous success – Z80. IBM had been pushing APL as the future, and it was incumbent on competitors to provide an APL offering.

Phil and Dave Crossley will have been the instigators of recruiting John Scholes, who had also been at Atkin’s, and teaming him with me to develop Dyalog (Dyadic + Zilog). Dave provided the management overview of that project while Phil and Ted had to worry about financing John and I, who were not bringing in consultancy money. It was at this point that Dyalog APL became a UNIX and C project. It was much later when I read Dennis Ritchie’s obituary that I realised just how early we had got into UNIX and C.

Dyalog APL was not the instant success that Dyadic hoped for. It had increased costs. We needed an office and the paraphernalia that goes with selling a product rather than brains. Dyadic ran into financial issues and was taken over by Lynwood Scientific, who made terminals with Zilog Z8000 chips inside. I think they really wanted the Z8000 expertise that John and I had acquired. As part of that takeover Phil, Ted and Dave had to leave with a derisory pay-off and I lost touch until I learnt of his death a fortnight ago.

From the perspective of APL language development Phil is not a tower of strength. However, from the perspective of having provided the impetus and drive to get Dyalog APL developed, he is very important.

NOTE: For anyone interested in reading more about the early days of APL, see the Vector special on the first 25 years of Dyalog Ltd.

Follow

Follow