The following are my attempts at the Phase I problems of the 2018 APL Problem Solving Competition. There are not necessarily “right answers” as personal style and taste come into play. More explanation of the code is provided here than common practice. All solutions pass all the tests specified in the official problem description.

The solutions for problems 1 and 3 are due to Brian Becker, judge and supremo of the competition. They are better than the ones I had originally.

1. Oh Say Can You See?

Given a vector or scalar of skyscraper heights, compute the number of skyscrapers which can be seen from the left. A skyscraper hides one further to the right of equal or lesser height.

visible ← {≢∪⌈\⍵}Proceeding from left to right, each new maximum obscures subsequent equal or lesser values. The answer is the number of unique maxima. A tacit equivalent is ≢∘∪∘(⌈\).

2. Number Splitting

Split a non-negative real number into the integer and fractional parts.

split ← 0 1∘⊤The function ⍺⊤⍵ encodes the number ⍵ in the number system specified by numeric vector ⍺ (the bases). For example, 24 60 60⊤sec expresses sec in hours, minutes, and seconds. Such expression obtains by repeated application of the process, starting from the right of ⍺: the next “digit” is the remainder of the number on division by a base, and the quotient of the division feeds into the division by the next base. Therefore, 0 1⊤⍵ divides ⍵ by 1; the remainder of that division is the requisite fractional part and the quotient the integer part. That integer part is further divided by the next base, 0. In APL, remaindering by 0 is defined to be the identity function.

You can have a good argue about the philosophy (theology?) of division by 0, but the APL definition in the context of ⍺⊤⍵ gives practically useful results: A 0 in ⍺ essentially says, whatever is left. For example, 0 24 60 60⊤sec expresses sec as days/hours/minutes/seconds.

3. Rolling Along

Given an integer vector or scalar representing a set of dice, produce a histogram of the possible totals that can be rolled.

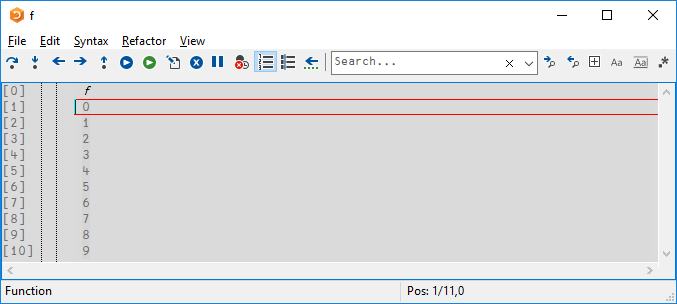

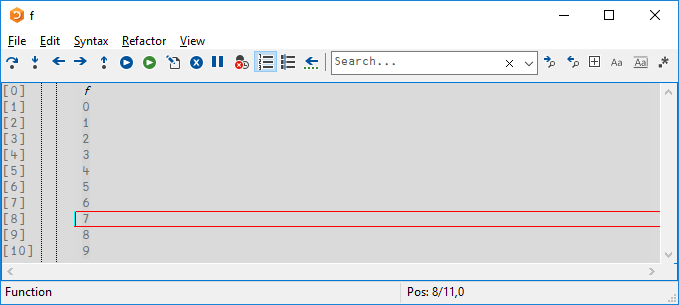

roll ← {{⍺('*'⍴⍨≢⍵)}⌸,+/¨⍳⍵}

roll 5 3 4

3 *

4 ***

5 ******

6 *********

7 ***********

8 ***********

9 *********

10 ******

11 ***

12 *⍳⍵ produces all possible rolls for the set of dice (the cartesian product of ⍳¨⍵) whence further application of +/¨ and then , produce a vector of all possible totals. With the vector of possible totals in hand, the required unique totals and corresponding histogram of the number of occurrences obtain readily with the key operator ⌸. (And rather messy without the key operator.) For each unique total, the operand function {⍺('*'⍴⍨≢⍵)} produces that total and a vector of * with the required number of repetitions.

The problem statement does not require it, but it would be nice if the totals are listed in increasing order. At first, I’d thought that the totals would need to be explicitly sorted to make that happen, but on further reflection realized that the unique elements of ,+/¨⍳⍵ (when produced by taking the first occurrence) are guaranteed to be sorted.

4. What’s Your Sign?

Find the Chinese zodiac sign for a given year.

zodiac_zh ← {(1+12|⍵+0>⍵) ⊃ ' '(≠⊆⊢)' Monkey Rooster Dog Pig Rat Ox Tiger Rabbit Dragon Snake Horse Goat'}Since the zodiac signs are assigned in cycles of 12, the phrase 12| plays a key role in the solution. The residue (remainder) function | is inherently and necessarily 0-origin; the 1+ accounts for the 1-origin indexing required by the competition. Adding 0>⍵ overcomes the inconvenient fact that there is no year 0.

Essentials of the computation are brought into sharper relief if each zodiac sign is denoted by a single character:

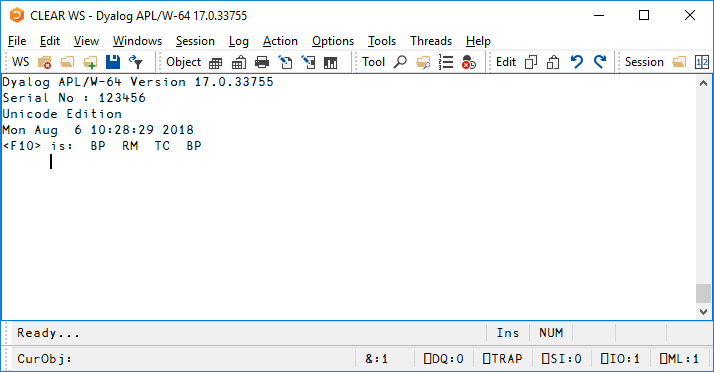

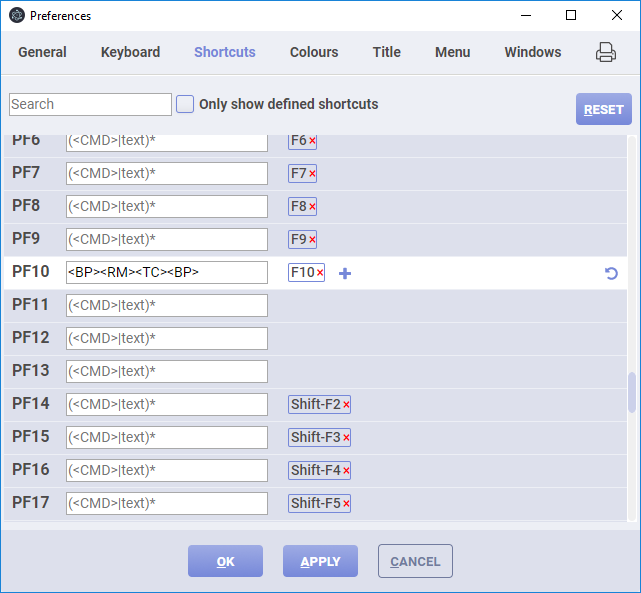

zzh ← {(1+12|⍵+0>⍵)⊃'猴雞狗豬鼠牛虎兔龍蛇馬羊'}The Chinese Unicode characters were found using https://translate.google.com and then copied and pasted into the Dyalog APL session.

5. What’s Your Sign? Revisited

Find the Western zodiac sign for a given month and day.

zodiac_en←{

d←12 2⍴ 1 20 2 19 3 21 4 20 5 21 6 21 7 23 8 23 9 23 10 23 11 22 12 22

s←13⍴' '(≠⊆⊢)' Capricorn Aquarius Pisces Aries Taurus Gemini Cancer Leo Virgo Libra Scorpio Sagittarius'

(1+d⍸⍵)⊃s

}For working with irregular-sized non-overlapping intervals, the pre-eminent function is ⍸, interval index. As with the Chinese zodiac, essentials of the computation are brought into sharper relief if each zodiac sign is denoted by a single character:

zen←{

d←12 2⍴ 1 20 2 19 3 21 4 20 5 21 6 21 7 23 8 23 9 23 10 23 11 22 12 22

(1+d⍸⍵)⊃13⍴'♑♒♓♈♉♊♋♌♍♎♏♐'

}The single-character signs, Unicode U+2648 to U+2653, were found by Google search and then confirmed by https://www.visibone.com/htmlref/char/cer09800.htm. It is possible that the single-character signs do not display correctly in your browser; the line of code can be expressed alternatively as (1+d⍸⍵)⊃13⍴⎕ucs 9800+12|8+⍳12.

6. What’s Your Angle?

Check that angle brackets are balanced and not nested.

balanced ← {(∧/c∊0 1)∧0=⊃⌽c←+\1 ¯1 0['<>'⍳⍵]}In APL, functions take array arguments, and so too indexing takes array arguments, including the indices (the “subscripts”). This fact is exploited to transform the argument string into a vector c of 1 and ¯1 and 0, according to whether a character is < or > or “other”. For the angles to be balanced, the plus scan (the partial sums) of c must be a 0-1 vector whose last element is 0.

The closely related problem where the brackets can be nested (e.g. where the brackets are parentheses), can be solved by checking that c is non-negative, that is, ∧/(×c)∊0 1 (and the last element is 0).

7. Unconditionally Shifty

Shift a boolean vector ⍵ by ⍺, where positive means a right shift and negative means a left shift.

shift ← {(≢⍵)⍴(-⍺)⌽⍵,(|⍺)⍴0}The problem solution is facilitated by the rotate function ⍺⌽⍵, where a negative ⍺ means rotate right and positive means rotate left. Other alternative unguarded code can use ↑ or ↓ (take or drop) where a negative ⍺ means take (drop) from the right and positive means from the left.

8. Making a Good Argument

Check whether a numeric left argument to ⍺⍉⍵ is valid.

dta ← {0::0 ⋄ 1⊣⍺⍉⍵}This is probably the shortest possible solution: Return 1 if ⍺⍉⍵ executes successfully, otherwise the error is trapped and a 0 is returned. A longer but more insightful solution is as follows:

dt ← {((≢⍺)=≢⍴⍵) ∧ ∧/⍺∊⍨⍳(≢⍴⍵)⌊(×≢⍺)⌈⌈⌈/⍺}The first part of the conjunction checks that the length of ⍺ is the same as the rank of ⍵. (Many APL authors would write ⍴⍴⍵; I prefer ≢⍴⍵ because the result is a scalar.) The second part checks the following properties on ⍺:

- all elements are positive

- the elements (if any) form a dense set of integers (from

1to⌈/⍺) - a (necessarily incorrect) large element would not cause the

⍳to error

The three consecutive ⌈⌈⌈, each interpreted differently by the system, are quite the masterstroke, don’t you think? ☺

9. Earlier, Later, or the Same

Return ¯1, 1, or 0 according to whether a timestamp is earlier than, later than, or simultaneous with another.

ts ← {⊃0~⍨×⍺-⍵}The functions works by returning the first non-zero value in the signum of the difference between the arguments, or 0 if all values are zero. A tacit solution of same: ts1 ← ⊃∘(~∘0)∘× - .

10. Anagrammatically Correct

Determine whether two character vectors or scalars are anagrams of each other. Spaces are not significant. The problem statement is silent on this, but I am assuming that upper/lower case is significant.

anagram ← {g←{{⍵[⍋⍵]}⍵~' '} ⋄ (g ⍺)≡(g ⍵)}The function works by first converting each argument to a standard form, sorted and without spaces, using the local function g, and then comparing the standard forms. In g, the idiom {⍵[⍋⍵]} sorts a vector and the phrase ⍵~' ' removes spaces and finesses the problem of scalars.

A reasonable tacit solution depends on the over operator ⍥, contemplated but not implemented:

f⍥g ⍵ ←→ f g ⍵

⍺ f⍥g ⍵ ←→ (g ⍺) f (g ⍵)A tacit solution written with over: ≡⍥((⊂∘⍋ ⌷ ⊢)∘(~∘' ')). I myself would prefer the semi-tacit ≡⍥{{⍵[⍋⍵]}⍵~' '}.

Follow

Follow